Part one of a two-part retrospective on the 1983 adult film

Porn is a participatory genre. The actors onscreen are rarely more than a few degrees removed from the mindset of its own viewing audience. The audience and the actors work in tandem to create an experience that other films simply cannot give you, provided that our suspension of disbelief is unacknowledged. The narratives of the genre and the performances found within end up being a lie agreed upon.

Can pornography produce art, then? Beyond the simple logic that all filmmaking is art (which I firmly believe), can it achieve that secondary definition of “art” we use to designate for pieces of art that are actually worth’s a viewer’s time? If you, the reader, have already seen the film Corruption, then you already know the answer to that question.

Roger Watkins is perhaps most famous for making Last House on Dead End Street, though he wouldn’t collect on that notoriety until a few decades later. When the film was released in 1977, the credited director/writer was “Victor Janos,” a pseudonym that never made another appearance. Reportedly Watkins finally took credit for making the film on an internet message board in the early 2000s. His claim was subsequently confirmed, and The Last House on Dead End Street still endures as a cult classic to this day, and will almost certainly be covered on this site at a later date.

That sense of fatalism that pervaded his first film, followed Watkins as he went on to his more prolific run as an expressively oblique adult filmmaker. Corruption is pornography by way of David Lynch. It’s dark, brooding, and has such a surrealistic bent, that the film never quite lets the viewer in on its intentions. This is declared almost immediately after the title card, as the first set of images we’re treated to purposefully disorient the viewer’s sense of time and space. We see our protagonist descending into an illuminated cellar of sorts (immediately signaling the dream logic that the film will adhere to for the duration of its runtime), only to cut to the same character on the (presumably) top floor of a commercial skyscraper where business is being conducted. Within the span of a single cut, viewers are no longer able to trust the typical editing rhythms of standard adult fare.

This business meeting features some incredible line-readings, even by hardcore standards. It starts with a proclamation.

I believe in business. I believe in honoring my contract. I believe that without honor, all business becomes quite useless.

A desolate-looking Jamie Gillis (who is referred to as Williams) delivers these lines to nobody in particular. As he looks out of the window into the endless fog swallowing the building he has found himself in, his words start to take on new meta-textual meaning. As LHODES showed, Watkins is no stranger to meta-influenced narratives, as that film centered around a filmmaker (one who dabbled in both stag and snuff) getting in way too deep. The same can be said about Corruption. Not on a literal level, per se, but numerous references are made to this otherworldly dimension, not between time and space, but between voyeurism and participation. That damn Twilight Zone area that regular porn viewers find themselves caught between every time they spin a blue reel.

Williams’ affirmation of business and honor can thus be read as Watkins’ upfront intention and declaration of taking his art seriously. I had never particularly cared for what little I’ve seen of Jamie Gillis’ performances throughout an admittedly impressive and illustrious career as one of the premiere male adult film stars, until I saw his droll existentialist turn as Williams. In Williams, he finds a vessel for his affectations that elevate what could have been a thankless role into an engaging rumination on the nature of the sinister intersection between sexuality, power, and vulnerability.

Onto the narrative actually transpiring, though… Williams owes a debt. In this case, the debt is owed to a couple of goons in business suits. Their occupation is never explicitly revealed, but an element of crime hangs over the entire picture. (The facade of a legitimate business dealing with under-the-table services is an apt description of the public perception of the porn industry at large. This cannot be overlooked) Williams sends a worker named Alan in his place to collect something undisclosed to the audience.

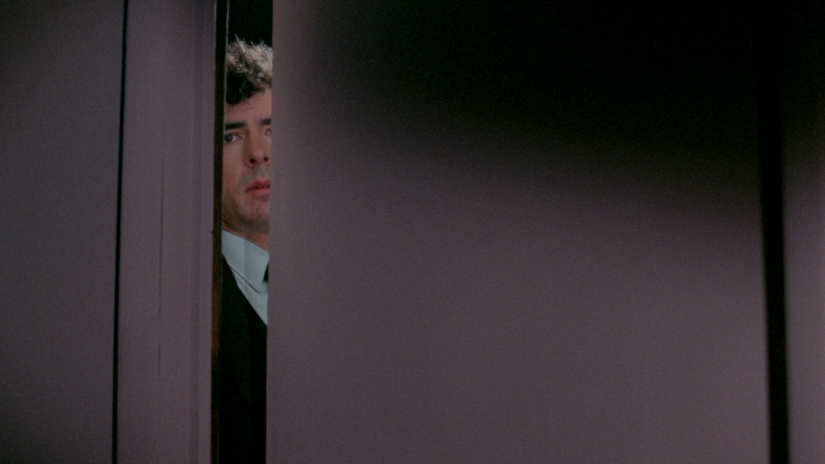

When he arrives, Alan stumbles through a revolving arsenal of framing devices. Once again nudging the viewers into a voyeur’s state of mind. First through a window, and then brightly enveloped by individual panes. Alan is portrayed by George Payne, and for the uninitiated, he can be mistaken for Jamie Gillis by a newcomer to the genre. This striking resemblance is almost certainly intentional, as it begets the tension surrounding fractured selfs and the many layers of one’s identity. Alan shouts to see if anybody is present in this warehouse.

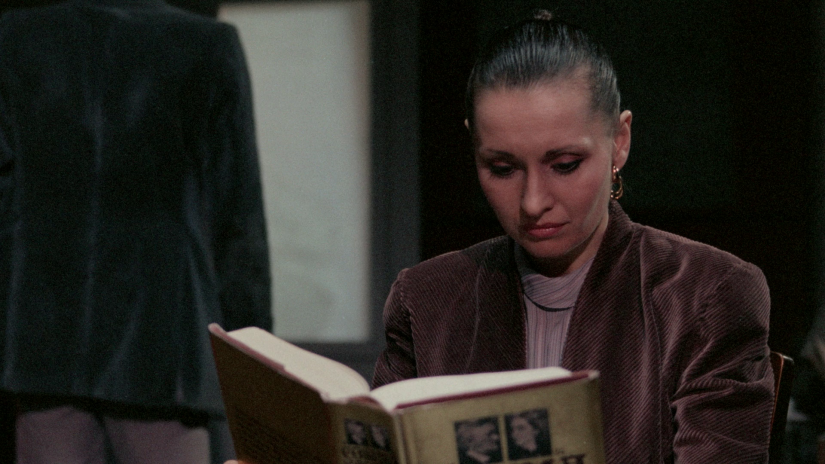

When Alan finally finds something of interest, it’s merely another entrance. One facilitated by a woman behind a desk. “Of course there’s someone here,” the woman shouts back. A glib call-and-response meant to remind Alan, and the audience that there is more to this than what we see at first glance. After exchanging cryptic words about seeking what he came for (including a reference as to how it’s not for Alan, but Williams himself), The Woman Behind the Desk warns that it “won’t be easy to getting it to where it belongs.” Alan is then unceremoniously guided towards the door behind the woman. Beyond that door, lies a bravura series of sequences that dreamily literalize the sedimentary nature of one’s consciousness when faced with pornography. It is important to dissect these sequences in isolation from the rest of the film, as they comprise a mini-thesis of their own.

Alan journeys through a series of three rooms. The most striking element of these rooms is the color that dominates not only its interior, but also the women who inhabit them.

The three rooms play out like a three-act Lynchian take on one’s subconscious reconciliation with sexuality and pornography. In the Blue Room, Alan is confronted with a sterile act of voyeurism. The Girl in Blue (Tanya Lawson) teases Alan with a display of hedonism that is derived solely from herself. “You know what I want you to do, Alan?”

“What?”

“Nothing.”

The Blue Room + The Girl in Blue = Blue Balls. It’s here the audience is confronted with the first-glance reality of pornography. That we are put-upon voyeurs who are unable to interact with the scintillating act of eroticism before us. The Girl in Blue denounces all men and asks Alan if he can do the same: denounce sexual contact with anyone who isn’t himself. He guesses so. She’s not impressed. Alan leaves a dissatisfied-looking Girl in Blue behind and ventures on to the next room.

In the Red Room, the Girl in Red (Marilyn Gee) allows Alan a bit more participation. She requests to be eaten out, and a willing Alan obliges. Before she returns the favor, the Girl in Red demands that Alan inform her when he’s going to come. He fulfills this request, and the Girl in Red promptly stops and even finagles her fingers in such a motion from her tongue to his tip, as if she was dousing the wick of a match before it burns too brightly. This room not-so-subtly evokes the tension that comes from viewing pornography: that salacious push and pull between trying to line up one’s own passionate participation with the slight disconnect that a viewer experiences when the other parties are not beholden or interested in your own individual needs for a rhythm that conforms to your own personal road to climax.

It’s in this room that Alan is essentially asked to denounce what’s ostensibly the whole purpose of sex, masturbation, and pornography itself: the act of climaxing. If the Blue Room acted as a declaration of individualism, in how Alan is forced to denounce others, the Red Room serves as a further commitment of this train of thought: to accept the journey as its own reward. This in and of itself is much like the sales-pitch of pornography as an art form: to simply enjoy the ride and to understand that a feeling of wanting more is a byproduct of consuming such a medium. After all, Alan does far more going than coming in this journey of the Three Rooms.

Alan is promptly dismissed, and he embarks into one last room.

The Black Room, or the room of no return (doors are not even glimpsed in this realm) houses one last female. The Girl in Black starts her foreplay with a Faustian promise of power should Alan follow one stipulation: the denouncement of love. This is the third and final denouncement that Alan agrees to, upon which is finally rewarded with penetration and climax. No longer on the outside, Alan is able to finally able to actively participate in that in which he seeks. The denouncements made prior to this act are all key in getting Alan to a place in which he is able to perform. A place that the Woman Behind the Desk warned would be hard to get to. To engage with pornography as a piece of art requires this three-part strategy of denouncing all of the pleasures that typically comes with the engagement of art: a community, a rewarding resolution, and love.

Now we all know that pornography is not actually as toxic as this mentality described in this essay (no matter what a puritanical society will have you believe). Nor am I arguing that Watkins was intentionally setting out to deconstruct the social stigmas surrounding one of the world’s most misaligned art forms. But I doubt that an artist as talented as Watkins was not at the very least subconsciously fighting these preconceptions when he made a film like Corruption. His brand of refusing to immediately serve the raincoat crowds ostensibly turns the film’s musings inwards and ends up meditating on its own existence and placement within a very particular film canon. While this may seem like Watkins is out to prove something, he’s also not afraid to simply use his sex scenes to comment on the nature of sexuality in general, pornography aside.

If we look at the dialogue that is present in the Black Room, we can see more traces of this fatalistic view of sexuality. A cynical exchange ensues as the Girl in Black (Tish Ambrose) declares that men have to give up something, in order to gain something. This binary lens of looking at love and power is certainly prevalent in today’s society. One cannot exist while the other one is in play. The reward for selling out love in favor of power? Sex. While this may seem like a cynical approach to sexuality, it is not completely unfounded (nor is it by any means encompassing). It’s merely an observation. It’s that act of seeing without influencing that Corruption continually brings up with regards to its eroticism. How can we truly participate in an act that demands performance if we’re too busy being seduced by the voyeurism aspect of it all.

Of course, this is merely one view of sexual intercourse (passionless, didactic, and ultimately fruitless), but it is a common archetype nonetheless. Both in fiction, and in real life. Corruption seems to be interested in depicting that bluntly, instead of attempting to veer away from such depressingly morbid views on sexuality. Watkins uses this room to express the ultimate reality of sexuality and pornography: indulgence in one set of needs causes a suppression of an entirely different set. That is not to say Corruption is anti-pornography. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. The film acts as a repudiation to a mainstream audience who doesn’t view pornography as art, by both indulging in that cynical view and later deconstructing the art behind neuroses that give way to that uninformed viewpoint.

Part two of this article will continue the discussion of Roger Watkins’ Corruption by focusing on the rest of the film and how it rejects and enforces the ideas presented in the Three Rooms.

1 thought on “Three Rooms: The Art of Roger Watkins’ Corruption”

Comments are closed.